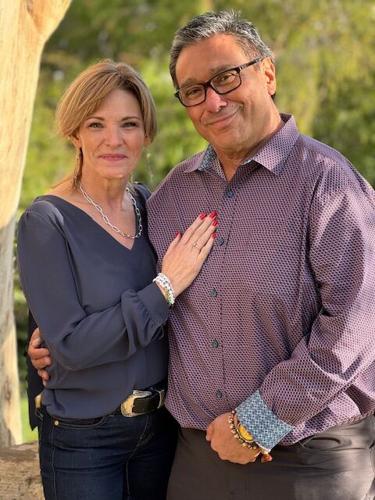

Columbine survivor Kiki Leyba calls his marriage a "Traum-Com."

He’s not being trite.

The veteran English teacher is confronting the struggle that the 1999 mass shooting caused for his marriage through humor and honesty.

“It’s a hell of a love story,” said Kallie Leyba, his wife of 23 years.

Saturday marks the 25th year since two students walked into the Littleton school, killed 12 students and a teacher and wounded 20 others. In the years since Columbine, there have been 404 school shootings, according to tracking from The Washington Post, exposing 370,000 students and school personnel to the trauma of gunfire. Some of those shootings did not involve injury. The federal government does not keep numbers on school shootings.

Columbine

April 20, 1999, was a morning of celebration for Kiki Leyba. Columbine High School principal Frank DeAngelis had just welcomed him as a new English teacher and he was in love with Kallie Snyder, who taught first grade at another Jefferson County public school.

But life took a turn, just as it seemed to be falling into place.

As Leyba and his new boss discussed plans, an administrative secretary knocked on the office door.

“She said that it was coming over the radio that there were shots fired in the Commons,” Leyba remembered. “It took a moment to register what I was hearing.”

That sound was rapid gunfire coming from the hall. He then saw a silhouette of a person, holding a long gun across his body. He doesn’t know whether that gunman was Dylan Klebold or Eric Harris. Not that it matters.

“They’re the least important part of the story,” he said.

Moving on

Leyba remembers DeAngelis running toward the gunfire, the booms getting louder and closer. The brand-new teacher thought to help usher frightened students to safety. As he ran to warn other teachers, a bullet missed him and hit a student in the leg.

After leading another group of students in an academic area away from the gunshots, he exited the building, grabbed his cellphone from his car and sent an urgent page to Kallie, who had no idea about the horror that was unfolding

He assured her in the moment he was OK. But he wasn't. And he wouldn't be.

Psychological trauma

Leyba wasn’t physically injured at Columbine, but he and many of the 1,400 students and teachers in the building would become psychological victims, doomed to traumatic stress and worse. When the school body walked through the repaired school the next year, Leyba described it as “the world’s largest psych unit.”

Add to that number the thousands of loved ones who lived with Columbine’s PTSD victims, people like Kallie, and the Leyba's children, and there's a festering stew that first responder psychologist John Nicoletti calls “vicarious trauma.”

Nicoletti doesn’t compare victims’ different levels of trauma according to how acutely they experienced a mass violence event.

“Trauma is trauma, no matter how the person was contaminated. The important factor is that the person gets connected to a mental health provider that is both trauma-informed and has experience working with individuals from mass violence events,” he said.

Nicoletti, whose brother was a Denver police officer, started Nicoletti-Flater Associates with his wife, Lottie Flater, in 1975. The firm staffs clinicians especially trained to counsel first responders.

Nicoletti and Flater were prepared for Columbine more than two decades before it happened.

On April 20, 1999, just before lunch, Nicoletti's pager beeped and he was on scene within minutes.

Ready to run

Kiki Leyba did not get home until late that evening. He spent his first post-Columbine night in a hyper-vigilant state, suspicious of people in parked cars and unfamiliar sounds. He began to sleep with his leg half out of the covers and his keys nearby in case someone came after him.

At the same time, he was dealing with the grief of losing the victims. He had taught and coached a couple of them before becoming a Columbine staff member. He attended three funerals, including that of 17-year-old Corey DePooter, where he hit a breaking point.

"I can’t bury more kids. I can’t do this,” he said, reliving the moment in a documentary called "Columbine 2024: 25 Years of Trauma." “There was real pain and trauma beneath the surface that wasn’t being completely dealt with … yet.”

Leyba descended into profound depression.

Still, he stayed at Columbine. He and Kallie were married in 2002. The couple had their first child and for the next four to five years, he was a walking and functioning classroom teacher.

“It wasn’t debilitating, but Kallie realized that I was experiencing symptoms of depression and PTSD,” he said.

But when the Class of 2002 graduated, the kids who were freshmen during the massacre were gone, leaving “a bunch of screwed up teachers behind.” Leyba was not prepared for that split to affect him like it did.

“It was so lonely,” he said.

He suffered from anxiety attacks and would lay behind his desk in the dark at the end of the school day with the lights turned off.

Kallie was lonely, too.

Five to seven years post-Columbine, Kiki Leyba was not the same man she fell in love with. His weekends were spent coaching lacrosse and mostly sleeping. He was on pills to control his moods and he wasn’t mentally present for his family, Kallie shared.

She did her part, holding the family together by quitting her job as an educator to focus on her new role as a mother of one and stepmother of two. She opened a home day care and preschool, which was “one of the hardest things I’ve ever done in my life.”

She cooked, cleaned, mowed the lawn, did the taxes and didn’t feel it was her place to complain. After all, she wasn't at Columbine when the shooting happened.

Early on, Leyba's therapist warned Kallie that the stress would kill him. Some years later, she sat him down on the stairs of their home and told him he needed to get help.

He said he would. Sure. During spring break. He would do that.

“I said tomorrow,” said Kallie.

That was around 2005.

Sandy Hook

Sometimes, the Leybas find they measure their wellness in terms of when other school shootings happened.

When did things start to feel better?

“I really think it was around the time of the shooting in Sandy Hook,” said Kallie.

It was December 2012 when 20 children and six adults were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut.

Twenty-five years after the shooting, Columbine is a special community that incoming freshmen might not recognize or embrace at first, Leyba said.

"We are a family and we care for each other and at some point, they get it," Leyba said.

As for the students from the era of the shooting, "after 25 years, when they come home, they still visit their high school to connect with those teachers who were important in their lives," he said.

Between students who came back to teach at Columbine and a few educators like himself who have been there since 1999, Leyba believes there are about a dozen originals who work there.

Kallie Leyba is now the executive director of AFT Colorado, the statewide teachers' union.

Their kids are grown.

The half-hour documentary, "Columbine 2024: 25 Year of Trauma," did not have a viewing date at the time of this writing. The Leybas are speaking out after all of this time because they see theirs as a love story that prevailed.

They hope it brings validity and solace to others who are experiencing PTSD and are afraid of what might happen.

"It takes work," said Kiki Leyba. "Kallie saved my ass."

On Columbine's 25th remembrance, Kalle is going to get a Columbine flower tattoo at a shop owned by a survivor's brother.

For Leyba, a tattoo is a commitment, so he wants to be sure. One day he may ask them to ink a phoenix rising.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.