Nothing should grow here.

Late-summer storms hurl hail against the granite slope. The dawn air freezes all but six weeks of the year. There is no sign of soil.

But on this lonely ridge, the oldest known tree in the Pikes Peak region, a Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine, has been growing for about 2,050 years.

It probably got its start when a gray, jaylike bird called a Clark’s nutcracker hid seeds filched from a nearby pine into a nook on the ridge, then forgot about the stash.

Today, the tree’s location is known to fewer than 10 people, who keep the route hidden to protect the ancient pine. The annual rings laid down in the stout trunk, however, are much more widely known. Decades ago, a local boy drilled a core sample no wider than a chopstick from the tree’s trunk that revealed the rings. Since then, scores of scientists have scrutinized the tiny dowel for insight into everything from ancient explosions to Aztec curses to global climate change.

So many have used the pine to study the climate that it has become a sort of global black box — a flight recorder for the past 2,000 years of Earth.

Colorful growth on the bristlecone pine tree that is believed to be the oldest in the Pikes Peak region. Photo Credit: Mark Reis

For all this, the pine doesn’t look like much. It’s about 15 feet tall. It has one living branch. Twenty centuries of storms have scoured all but 7 inches of bark off the 9-foot diameter trunk.

So much of the tree is dead, gray wood that it looks a bit like a rhino wearing a wreath. Still, like all old bristlecones, it seems to exude an enduring nobility.

“You feel like you are meeting a very important person, perhaps someone from mythology,” writer Darwin Lambert said of old bristlecones.

Another writer, Michael Cohen, said the ancient trees have a long-suffering beauty that can come only from the “beauty of suffering long.”

HIDDEN HISTORY

For most of the tree’s life, it stood unnoticed on its lonely ridge. Fires swept through. The tree survived. Miners cut down the surrounding forest. The tree was too twisted to be of use.

It might have gone on unnoticed if a 16-year-old kid from Colorado Springs named Craig Brunstein hadn’t spied the old tree in 1968 while hiking high in the mountains.

“I loved everything outdoors, and I was really into trees — identifying them, finding their ages. I guess I was sort of a nerd,” said Brunstein, who now works for the United States Geological Survey in Denver.

The friendly, gray-haired geologist is the one person who knows the locations of the oldest trees in Colorado because he is the one person who has spent decades finding them. He has such a fondness for the venerable pines that visitors to the backroom where he keeps all his cores can expect him to wave a chunk of bristlecone wood under their noses, smile and say, “Smell that. Doesn’t it just smell great? I love it.”

A marker left on a dead bristlecone pine is used to match it with records of old forest trees. Photo Credit: Mark Reis

When Brunstein started hunting trees, it was well-known that rings could reveal their age. Leonardo da Vinci noticed it in 1500. Henry David Thoreau wrote in the 1840s that through rings, it is “easier to recover the history of the trees . . . than to recover the history of the men who walked beneath them.”

But the past century saw the practice make huge leaps. In 1930, a scientist in Arizona used wood cores from Ancestral Pueblo ruins to suggest that the mysterious abandonment of Mesa Verde was caused by a long drought. In the 1950s, a group of scientists discovered a grove of bristlecones in California that was almost 5,000 years old, and, by overlapping cores from living and dead trees in the area, gradually built a tree-ring chronology dating back almost 9,000 years.

About the time Brunstein spotted his old trees, the rings of bristlecones proved that radiocarbon dating — the newest, most sophisticated way to measure an object’s age — was inaccurate by at least 1,000 years.

Brunstein read about each new find as a kid. To him, the potential of the old pines seemed almost limitless. The only trick was to translate the trees’ language.

After Brunstein found his grove of bristlecones, he borrowed a coring tool from his science teacher at Cheyenne Mountain High School and took samples. They suggested one tree was almost 1,000 years older than any tree found at that point in the Rockies — so old that when he told scientists at the top tree-ring laboratory in the country, the University of Arizona, they initially didn’t believe him.

In the summer of 1969, Brunstein convinced a scientist from Harvard University named Val LaMarche to come out and investigate the trees. LaMarche took several cores back to the lab, where he noticed an odd pattern. Under the microscope, the compact corduroy of rings revealed the normal alternating pattern of light bands of cells made each summer during the growing season and dark bands made at the end of the year as moisture drained from the living tissue in preparation for winter.

Shadows of needled branches are cast on the trunk of an ancient bristlecone pine. Photo Credit: Mark Reis

But the cores also showed dark bands where the cells were smashed and broken like a highway pileup. These were frost rings — scars left from years when the freezing weather came too soon and ice formed in the cells, shredding the thin walls.

An occasional frost ring isn’t unusual, but the cores from near Pikes Peak held almost 200, which gave LaMarche an idea. What if the cold snaps that formed the frost rings weren’t just random events? What if they were a barometer of much larger global catastrophes? He started comparing frost ring dates with other ancient events and was able to link the damaged rings to events on the other side of the world.

In 42 B.C., when the tree was just a sapling, Sicily’s Mount Etna exploded, spewing sulfurous gas into the sky. The sun grew pale for months, crops withered in Europe. Some Romans wondered whether the phenomenon was caused by the murder of Julius Caesar. There is a frost ring that year.

In 1815, Tambora volcano in Indonesia detonated in the largest eruption in recorded history, filling the air with dust that cooled the whole Earth. Farmers in New England called it “the year without a summer.” The cold, rainy weather caused author Mary Shelley to stay inside on her Swiss holiday and write the beginnings of the book “Frankenstein.” There is a frost ring that year.

In 1844, a year tribes and trappers in Colorado called “the time of the big snow,” storms dropped so much snow that when it finally melted, thousands of buffalo lay dead on the prairie. There is a frost ring that year.

The old trees form so many frost rings, Brunstein said, because they live at about 11,400 feet — the tree line, where the slightest temperature dip can form ice in the cells.

Brunstein has counted 182 frost rings in cores from the region, which, he said, “makes them one of the best indicators of global climate we have.”

The record is so complete that archaeologists have used it to help explain an Aztec curse. In 2004, an article in the journal of the American Meteorological Society used cores to make sense of the pre-Columbian belief that the first year in the 52-year Aztec calendar was always haunted, according to one colonial Spanish scribe, by “famine and death.” Old Aztec pictorial histories show the first year of every cycle plagued with storms and starvation. One drawing shows famine so severe that coyotes came into the city to devour the dead. Tree-ring data showed that the “curse” was probably caused by cyclical droughts and cold snaps.

Of the 13 cursed years on record, 10 had below-average tree-ring growth or frost rings that could have caused crop failures.

The frost damage isn’t limited to the distant past. In 1965, a strong El Niño weather pattern in the Pacific brought cold, wet weather to the Rockies, where a young Brunstein woke up to a “God-awful” September storm that dumped more snow than he had ever seen.

“And sure enough,” Brunstein said, “There’s a frost ring.”

THE LONG VIEW ON CHANGE

Recording storms is an insightful quirk of bristlecones, but their most useful contribution may be as evidence of how humans are heating up the atmosphere. In 2004, three climatologists from Penn State, the University of Massachusetts and the University of Arizona published a blockbuster study detailing average temperatures in the northern hemisphere for the past 2,000 years. The team used a broad array of natural record keepers to plot the changes — coral reefs, layers of ice, lake sediments and the bristlecones near Pikes Peak.

The results showed a relatively flat, stable temperature that suddenly climbed after 1900. The 1990s appeared to be the warmest decade in a 1,000 years.

The team blamed the rise on human-made greenhouse gasses.

As might be expected with a politically charged topic such as global warming, the results have been vigorously debated.

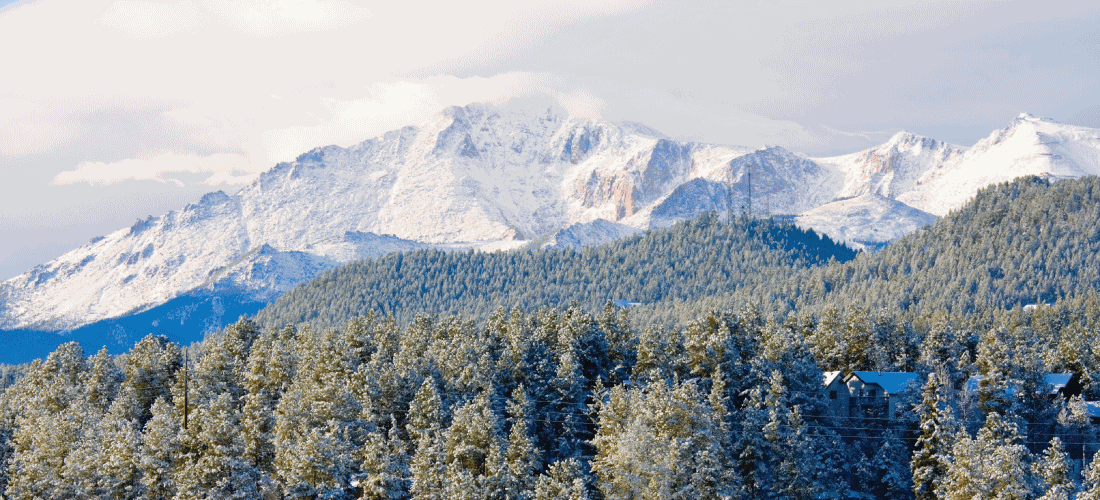

Bristlecone Pine Tree Believed to be 2050 Years Old near Pikes Peak.

The accuracy of many natural record keepers, including the trees, has been questioned. But most climatologists think the study gives a fairly accurate representation.

To make a stronger argument, the cores from near Pikes Peak are being used now by Matt Salzer, a tree-ring scientist from the University of Arizona, to create a more detailed study of past climate that he says will probably reinforce the first.

“There is still some uncertainty,” said Salzer. “The idea is to use more and more data to create a better model.”

Here’s what is certain: In 1900, bristlecones in Colorado started growing much faster. Studies suggest they are reacting to increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“There’s argument over whether that means there’s global warming,” Brunstein said with a shrug as he examined cores spread out on his table. “Personally, I believe it does.”

WILL THE ANCIENTS SURVIVE?

For a long time, Brunstein told almost no one about the trees — not even other scientists. He knew the oft-told story in bristlecone circles of the graduate student who cut down a bristlecone in 1964 to date it, then realized, after counting 4,862 rings, that he had killed the oldest living thing on Earth.

“People do strange things,” Brunstein said. “Even trained scientists.”

Then, in the late 1980s, a colleague warned that if he didn’t announce the trees’ existence, someone else (perhaps someone less careful) would go looking for them. So he published a brief article describing the pines while protecting their locations and told a U.S. Forest Service biologist where the trees stood, so managers could protect them.

Other people have asked for directions: photographers, hiking groups, scientists. Brunstein almost always says no.

“The best thing for the trees is to be left alone,” he said.

People may end up inadvertently killing the trees anyway. At the turn of the century, a mold called white pine blister rust piggy-backed here from Europe on a transplanted pine. The rust kills bristlecones. It reached Colorado in 1998. Scientists do not yet know how the rust affects local pines. High altitude may hinder it and protect the trees, but Forest Service studies suggest “regional extinction” is also possible.

Most likely, the trees will adapt. Individual trees have survived mini ice ages and severe drought.

Clouds fill the valley below the spot where a 2,050-year-old bristlecone pine grows near Pikes Peak. Photo Credit: Mark Reis

As a species, they’ve been in the Pikes Peak region longer than Pikes Peak. They live so long that they’ve given rise to an odd superstition among tree-ring researchers that men who study the ancient trees are doomed to die young. The scientist who discovered the oldest trees in the world in California died at 49. His successor, who proved radio-carbon dating was wrong, died at 64. The Harvard researcher who connected frost rings to ancient volcanoes died at 50. The next researcher to pick up the cores (who noted the jump in growth rate this century) died at 51.

The tree-ring community doesn’t put much stock in the superstition, Brunstein said. He has studied the trees for decades and hopes to live to 85. But the inspiration behind the rumor remains: People don’t last very long. The trees do.

Even a long-lived man will grow up, grow old, and die in less than an inch of dense bristlecone rings.

The span between the American Revolution and the testing of the atomic bomb is thinner than a good textbook. Standing next to a bristlecone forces a person to think in centuries.

Compared with the bent, stoic pine, most of the world is temporary. What seems like bedrock will inevitably crumble. And what will be left?

At dawn one morning, the first rays of light spilled over the prairie and bathed the rocky slope where the oldest tree stands. In the warm sunshine, its branch resumed the work passed down from a seed 2,040 years ago: use the light, grow new needles, draw water up from the rock.

This year, the branch produced 19 cones. The tiny seeds between the scales will probably be snatched up by a Clark’s nutcracker, or hidden in the rocks. Some will feed the birds. Some will be forgotten and have a chance to begin the work again.

GO TO THE GROVES

The oldest bristlecone groves are kept secret to protect the trees, but other groves, which harbor trees older than 1,000 years, are open to the public. The most picturesque and accessible are on Windy Ridge near Alma.

To get there, take U.S. 24 west from Colorado Springs and take Colorado 9 to downtown Alma. Look for a left turn to Kite Lake and Buckskin Gulch (County Road 8). Drive up a dirt road for 2.8 miles, then turn right on Forest Road 787 at the sign for Windy Ridge. The next 3.5 miles is rough but passable for most passenger cars and takes you to an abandoned mine site and a parking area.

From there, walk a half mile up the road. At the edge of treeline, the oldest trees grow, doubled over by the gales sweeping down from the peaks above.

No admission, no facilities.

*This article originally appeared in the Colorado Springs Gazette

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.